Summary

The project revolved around planning a path for a vehicle on a road, given a list waypoints that it needs to pass. There are three lanes and other vehicles could be driving on them, dynamically changing their speed and sometimes changing the lane as well. There are restrictions to the maximum acceleration and jerk that the car can have, and a requirement to stick as close to the speed limit as possible, changing lanes if needed.

At first glance, it seems like a simple project. However, after implementing the initial solution, relying on a quintic polynomial trajectory that minimizes the jerk of the car, I found that sometimes, even while going on a straight line, the car would suddenly gain a huge amount of speed to some direction, and would be violently launched far away from the road.

I’ve implemented another solution, using a spline library instead of a quintic polynomial to plot the trajectories, but I would still see the car misbehave.

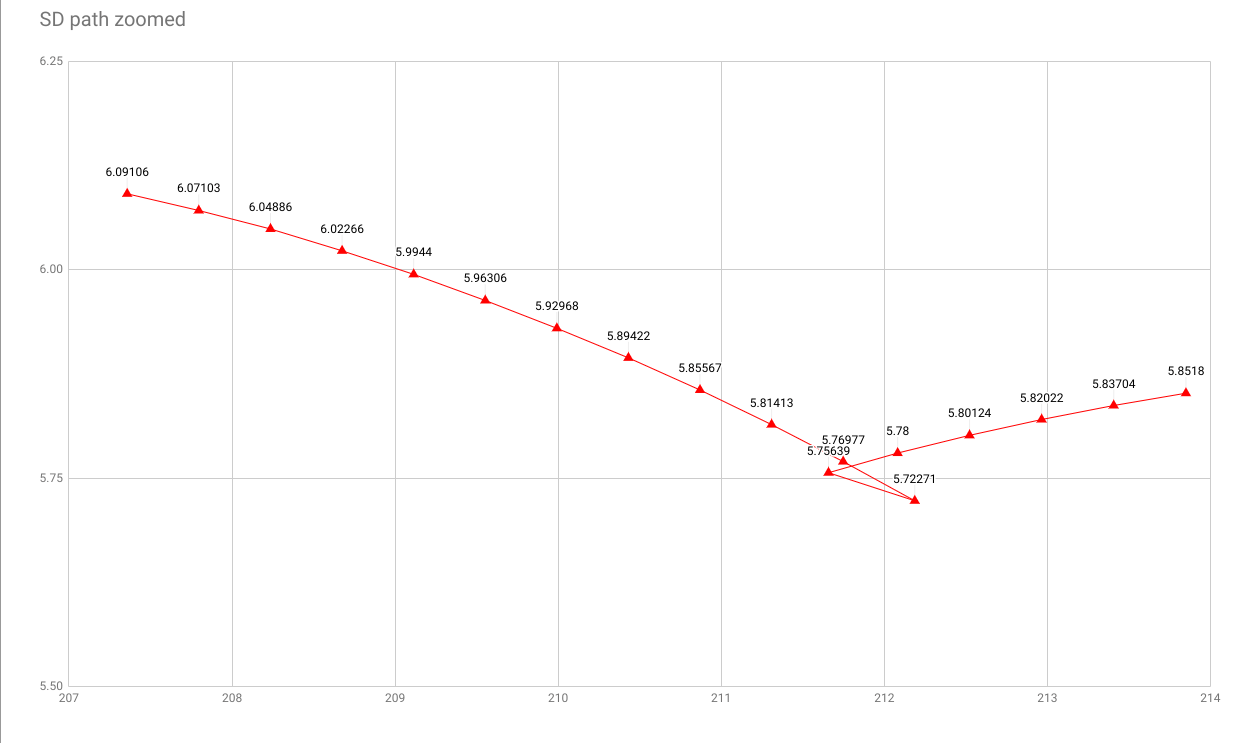

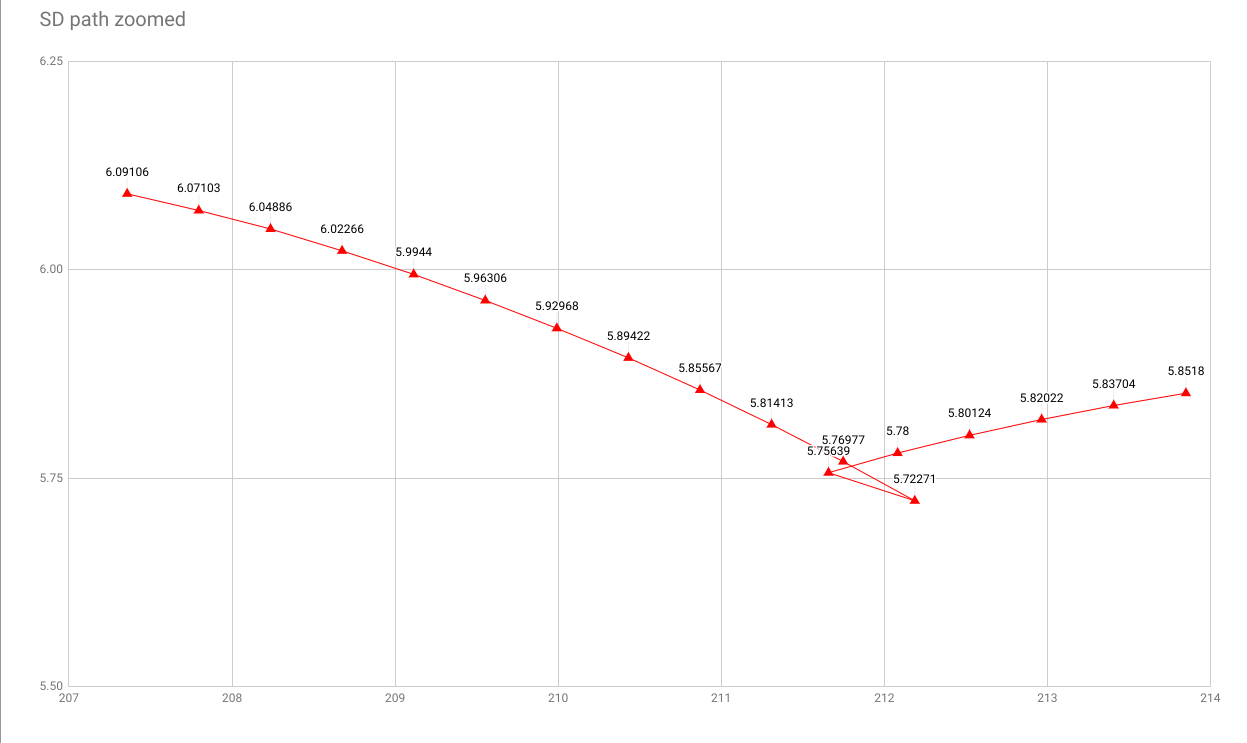

Finally, after days of debugging I realized that the transformation between XY coordinates and the Frenet Coordinates produced flawed results. Even if I’m going completely straight, the Frenet coordinate values are such, as if I was veering off to one side, and then back onto the road. In transformed Frenet coordinates on this erroneous turn, the next point B after the farthest point A is actually behind point A. If computing speed from these points, it all of a sudden shows as negative, launching the car off road. (Third picture above)

After discovering this, I fixed the code to avoid Frenet Coordinate transformation in all cases, except for determining destination point of the plotted path (since the transformation is still approximately correct).

There was another issue, where the speed of the car, returned by the simulator was incorrect in a similar way, but the fix was to just keep a pose history and compute the speed myself.

After 3 arduous weeks, I have managed to complete the project and produce a path that take the car around the track efficiently, changing lanes when necessary.

Methods

This section provides a full description of the solution.

Initial attempts and discovery of error in the simulator

Before talking about the path planning model, it might be useful to understand the context of the solution. The path selection problem is not that difficult to solve if you can estimate the problems you will encounter. This was not the case here, unfortunately.

While developing a quintic polynomial-based method of finding the optimal path wasn’t hard at all, as wasn’t dynamic lane changing, I never expected issues that I encountered afterwards. The car, while simply going straight, after around a minute or so of running time, would suddenly phase away from the track at high speeds, in a seemingly random direction. It took me a few weeks, but I managed to narrow it down to the getFrenet function. Apparently, even on a fairly straight road, with robot nearly following a straight line according to the simulator x,y coordinates, the s,d coordinates produced by getFrenet show a path leaning to the side, with a disjunction (sheet 2), that was causing the speed to suddenly become negative as the car was calmly driving along a straight road at high speed. This meant that I had to recode the solution to avoid getFrenet whenever possible.

The problem then was that the polynomial-based solution relied heavily on the s coordinates. Still, using splines wasn’t too problematic, except for figuring out how to nicely set the speed. The problem was that there was another fault with the simulator. The speed of our car was sometimes wrong. For example, in meters per second, the speed at every tick could go like this:

16.0 -> 16.5 -> 17.0 -> 11.5 -> 18.0 -> 18.5

Unfortunate. I had to find a way to use x and y to compute the speed myself. While I lost a few days looking for this issue, it wasn’t as complicated as the first one. After I cached the car speeds after every path point, it was pretty easy to get the right path afterwards.

The Path Generation Model

Here’s how my path generation code works:

It all stars in main.cpp, which initializes the map waypoint info and connects the asynchronous responses form the simulator to the handler function in pathPlanner.cpp. From here on, everything will happen in pathPlanner.cpp.

Generally, as can be in planPath (line 50), whenever we receive a response from the simulator, we:

- Add some of its response data to history. While still adapted to a legacy solution, we store some positions from the previous path in a double ended queue.

- Check if a lane change is needed and change the target lane if so.

- Plan a path to a distant point ahead of the car. And return the path to the simulator.

The path is then generated as follows. First, we wish to fit a spline between our start and end point. The main concern here is that it might differ significantly from out previous trajectory. So to make it smooth and inline with the past car poses, it we basically add the following points to it:

- All the points in our car history (up to 100!), that are far enough apart from each other (otherwise I found that the splines ‘burst’ outwards, to the left and right of the car.). Note that these historical points are saved at the end of each run, before the path is sent.

- The starting

x,ypoint of the car - A couple of points form the previously planned path, as returned by the simulator

- Two distant points at the end of the path, selected according to the maximum possible distance we can travel in 2.5 seconds. Here S coordinate is used, that was established to be intermittently erroneous. Still, given that this target point is far, the error matters less, assuming the point’s location is approximately correct.

The points are then transformed to the car’s frame of reference. The main purpose of this is to make the x coordinates sorted, as that’s what the spline library requires. The points are then used to create a spline.

Now, we generate the path of more or less the distance to the target point. The maximum speed that we allow ourselves is 45.00 MPH, but we also restrict ourselves to the speed of the car in front. We iterate over every time point (line 208) on the path, and referring to the previous speed, compute the next one by adding or subtracting constant speedup value (manually tuned). We cache the speeds generated after every timepoint, as that’s where we get our current speed from. As mentioned in the previous section, we definitely can’t trust the speed, returned from the simulator, and this is our workaround. After all this, the car points are converted to world coordinates and returned.

Lane changing

The other component maybe worth mentioning is the lane change bit. Briefly, we check if we’ve not carried out a lane change recently, look to the nearby lanes, and change if the attainable speed there is higher than in our current lane, and there’s no car blocking our way. There’s a restriction imposed of when the car can change lane again, as otherwise it drives recklessly by trying to change more than one lane at a time.

Other functionality

The implementation is held together by smaller bits of logic, but at this point, it would be a bit difficult to describe every workaround and functionality used. Especially if I also went into detail the the functions for the alternative solutions - 3 ways of computing kinematics, several ways of planning the path, potentially better car predictions (I’m not using any here). Feel free to browse through the code yourself - I hope you will find it sufficiently documented and understandable.

Code Repository: GitHub

Path Planning Video: YouTube

Sheets with getFrenet error: Google Docs